Berlinklusion’s Kate Brehme* reflects on “You Are Not Invited”, a protest action created by the organisation in 2019 at the Haus der Statistik. This ‘un-exhibition’ — an exhibition that no-one was invited to, was Berlinklusion’s exploration of the relationship between gentrification, the temporary use of non-arts spaces for cultural purposes, and the neo-liberal structures that perpetuate inaccessible working conditions for arts workers in Berlin.

Over the years, Berlinklusion — a Berlin based network of people with and without disabilities working toward greater accessibility in arts and culture — has operated without its own physical space. My colleagues Jovana Komnenic, Dirk Sorge, Kirstin Broussard and I have worked from our homes, from cafés, and with partner organisations in order to achieve our common goal: to offer inclusive and accessible arts events and projects in Berlin. We found ourselves in this situation because, like many other non-profit arts initiatives, we have struggled to find affordable spaces in the city within which to work. Moreover, what space is available and affordable — whether for producing exhibitions, staging events, running workshops, or giving access advice to arts organisations — is often inaccessible. The inaccessibility of these spaces often result in arts workers and audiences with disabilities being unable to participate in arts and culture at all. Considering that people with disabilities form the world’s largest minority, that most people will experience disability at some point in their lives, and that the overall numbers of people living in cities worldwide will also increase, this issue is one that affects us all.

For these reasons, when the former Haus der Statistik in Mitte was offered up last year as an affordable space to cultural workers as part of the city’s Pioniernutzung (Pioneer Use) programme, we jumped at the opportunity to find out what it would be like to create a real home for our activities, and a physical manifestation of the network of individuals and organisations we have built up since our foundation. We had originally proposed to curate a programme of pop-up exhibitions and film screenings with artists with disabilities in the form of a series of mini-residencies. We were especially drawn to the space because, unlike a lot of other arts and cultural spaces in Berlin, it was on the ground floor, it had a ramp at the main entrance and a disabled accessible toilet, and it was centrally located and within easy reach of public transport. In other words, it was relatively physically accessible.

Unfortunately, our actual experience of being in the space was far from accessible, both in terms of the physical building and the way it was being managed. The toilets in general were unhygienic and the only disabled accessible toilet was being used as a storage area. The passages leading from the main entrance to our space were partially blocked. But worse than this was the general sense of exclusion from the so-called community the space was supposed to engender. Communication from the facilitators at the Werkstatt was sketchy at best. Invitations to community meetings to get to know our neighbours and their planned initiatives came either at short notice or not at all, meaning that we weren’t able to fully participate or communicate our access concerns.

As we deliberated on how to proceed with our original idea for programming mini-residencies with disabled artists, we began to question the ways in which the lack of accessibility within the Pioniernutzung initiative were symptomatic of larger issues: in so-called participatory urban development projects such as this1 one, who, and what kind of bodies, are imagined as urban ‘pioneers’? Certainly not disabled ones. Furthermore, while it may be considered reasonable in some quarters for some cultural workers to spend hours of their own unpaid time and their own money renovating a shell of a room, without heating and properly working toilets, in order to pay a subsidised rate to use such a space, many disabled cultural workers simply don’t have that privilege. Our question then became: why can’t these government subsidised spaces for cultural use be planned and managed in a way that ensures that they can actually be used by everyone?

Untitled by Kirstin Broussard ©Jürgen Scheer

While our original idea had been to invite in artists with disabilities to respond artistically to this specific urban space, we decided, in the end, not to invite anyone at all, because we didn’t want to pass on and reproduce the inaccessible working conditions that we had encountered ourselves. Instead, we created a kind of protest exhibition in the space — an ‘un-exhibition’ — that no-one would ever be invited to. We had already paid our rent, so we decided to install our own artworks, document the exhibition, take it all back down again, and then shift the physical manifestation of the exhibition online, where at least it would be a more accessible experience for our viewers than at the Haus der Statistik. It was important to us that we used this space on our own terms. We scaled our efforts down and we didn’t buckle under the pressure to ‘perform’ a public act of artistic work that would only be of benefit in terms of the appearance of the Pioniernutzung initiative. We took the opportunities that this particular physical space gave us and used only the time in the space that was comfortable for our own individual bodies to collaborate with each other to create an experimental exhibition on our own terms. Together, we developed a broad theme of interconnectedness and correlations. My colleagues each selected pre-existing artworks from their practices, some recent, some older, that they felt resonated with the space, the paradigm of inaccessibility that we found ourselves in, and the broader themes of the exhibition.

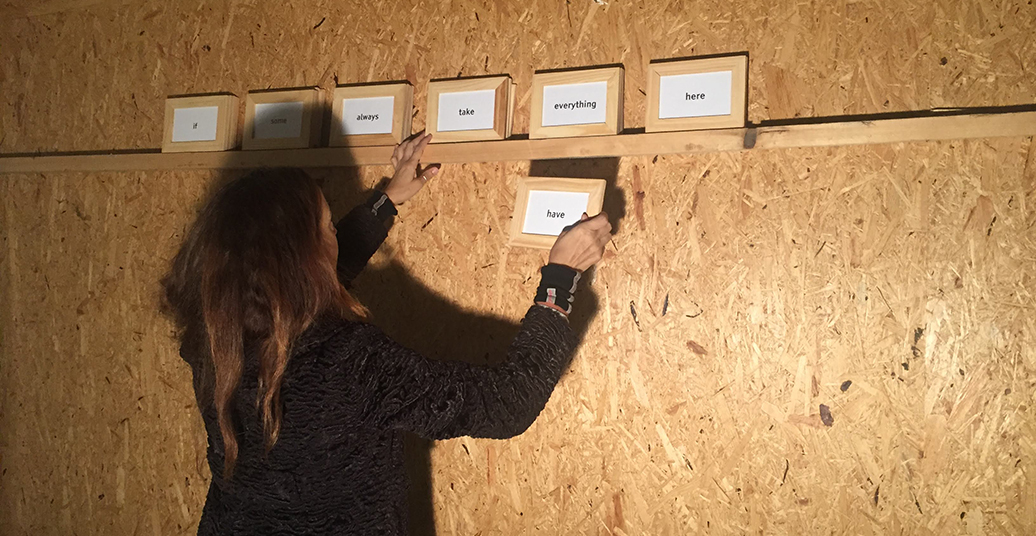

Dirk created Frames of Reference, a site-specific interactive installation comprising 36 printed words in small wooden picture frames that we displayed along the exposed wooden struts of an unfinished chipboard wall. The frames were re-arranged to form different sentences. The words come from six different categories: verbs, expressions for time, expressions for place, quantifiers for subjects, quantifiers for objects, and conjunctions. For example: “If some always have everything here”.

Kirstin’s five photo-collages from her series If One Were Two (2018 / 2019 ongoing) depicted rich landscapes, each one divided in two horizontally by a fine gold metallic thread. Our only indication of what separates above from below, or reality from reflection is the thread, connecting them literally and metaphorically and seeming to compress both space and time.

Jovana presented two works. First, a series of minimalist acrylic drawings and paintings on canvas and paper from 2018 called Water Land Heavenly Bodies which depicted a multitude of objects and perspectives, basic elements of a landscape such as the land, the water, the sun and the space itself, weaving themselves into a new whole with the potential of continuing to intertwine, to change and to expand. Her second work was a detail from a 2004 installation piece Contratto d’alloggio / Contract of Accommodation, a picture made from rusted iron frame, glass, print on paper and pvc, electro-motor, dust and dirt, referring to a neurological system in which all the cells are interconnected.

You Are Not Invited, exhibition view from outside ©Jürgen Scheer

Our small performative action was perhaps not what was expected of us when we occupied the tiny space offered to us at the Haus der Statistik and it was certainly not what we had originally planned. But we hope that, in some way, it will draw attention to the often exclusionary nature of such cultural urban development initiatives and encourage the facilitators of such projects to think of disabled bodies right from the very start so that such temporary affordable spaces can be used by everybody.

- I say so-called because the documents outlining the participatory process by which the Pioniernutzung initiative for Haus der Statistik was conceived does not seem to have involved any groups or communities reflecting the needs of people with disabilities, particularly those working in the cultural field. https://hausderstatistik.org/pioniernutzungen/