Review written by Nine Yamamoto-Masson.*

This performance was part of the festival Radical Mutation: On the Ruins of Rising Suns, curated by Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro, Saskia Köbschall, Tmnit Zere, in collaboration with Wearebornfree! Empowerment Radio, 23.9.–4.10.2020, HAU1+2+4.

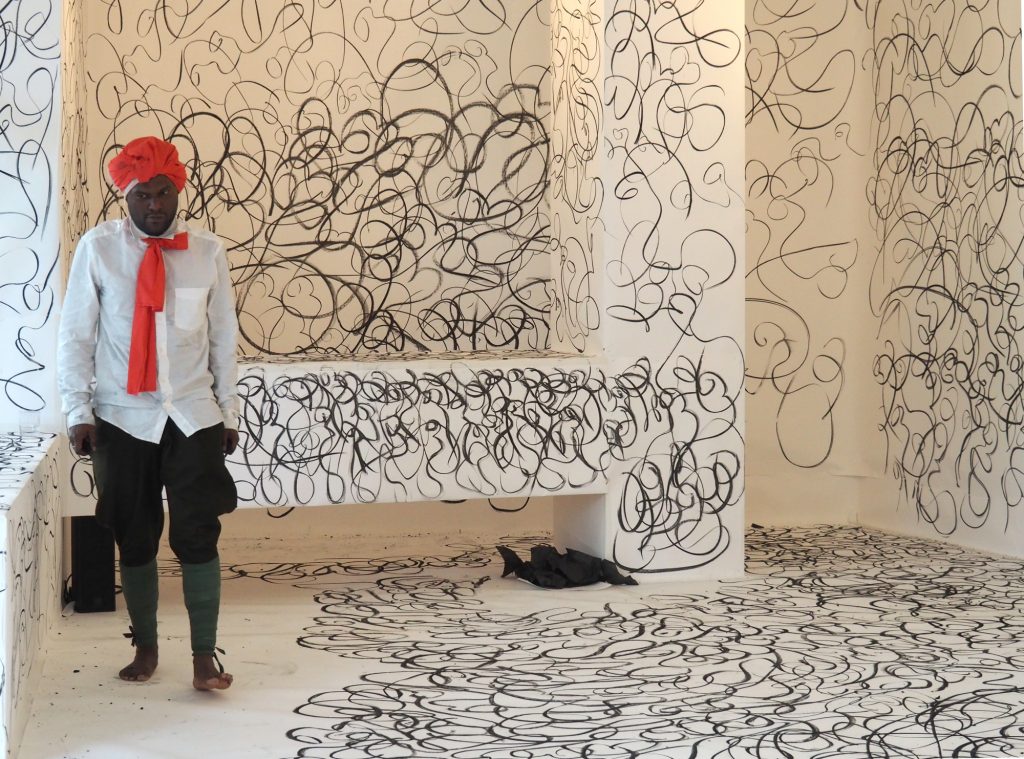

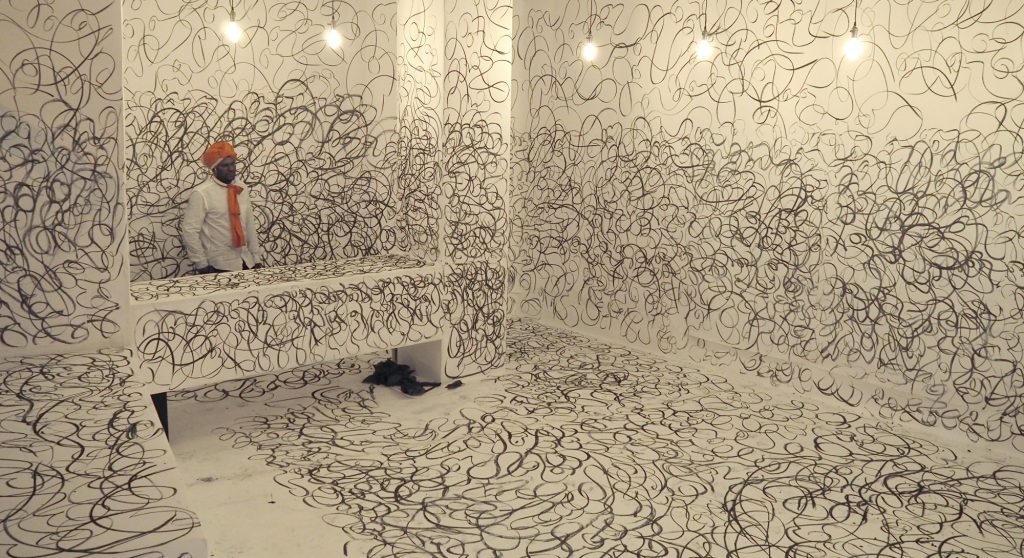

In restrained, slow, deliberate movements, Sajan Mani moves through the brightly-lit white cube, tracing, writing, drawing in charcoal on the paper that floors and walls of the space (the former HAU2 café, now in Covid-limbo) have been covered in. Over the two days of his durational performance Tyger von otherspur, he covers nearly the entire surface of the room. As he does so, his movements and their charcoal traces generate an entirely new space out of this limbo realm: an immersive drawing, a room that is also a text. A counter-metaphor that confidently asserts the opaqueness it knows itself to inhabit in this geographical and cultural context.

Audience members leave their shoes at the door and carefully step in, sometimes crushing small bits of charcoal left on the floor under their feet. Mani is barefoot, wearing a white shirt that has become dirty with charcoal, black pants, green ribbons tied around his calves, a long red scarf around his neck in a floppy bow, and a headdress made of red and off-white cloth wound around his head. A large gold-coloured hoop earring is attached to the fabric, right above the ear. His movements seem natural, improvised, but methodical. His focused gaze surveys the room, its surfaces, its negative space. When he traces the large, interlaced lines on the floor, lying down, his body smudges the charcoal. Later, he tells me that his movements in space are partly inspired by imagining non-human cosmologies such as that of the tiger, and by the millennia-old sacred ritualistic folk dance of his home state of Kerala, Theyyam.

Photo: Paris Helene Furst

On one of the walls, a three-channel video installation plays a 36-minute loop of black-and-white scenes culled from the thrice-produced two-part German cult film The Indian Tomb / The Tiger of Eschnapur, made in 1921, 1938, and 1959 (the latter by Fritz Lang, ex-husband of prolific writer Thea von Harbou, whose 1919 novel all three versions are based on, divorced Lang in 1933 to marry an Indian writer, joined the nazi party in 1940 and made films for the Third Reich). Three flatscreens show scenes of dazzling exotica, opulent papier-maché décors that denote The Mysterious East™, slithering arrangements of bodies bursting with erotic tension, disquieting facial expressions of pretend Indians. Intercut with these scenes is a classic 1950s TV cartoon ad for the famous German chocolate brand Sarotti, featuring its classic mascot, a racist caricature of a Black person with exaggerated features and colouring, always ecstatically rushing to serve someone something on a tray, dressed in a “turban” and other sartorial mash-ups of the “Orient”, the East, and Africa. Incidentally, the former Sarotti chocolate factory is just down the street: It is now a hotel and retro café operating under the company name, both proudly displaying their racist mascot on their walls.

The convoluted plot of the films can be summarised as: Tigers and evil cunning brown men want to destroy the helpless and scantily clad (light) brown woman, but she is saved by the heroic German engineer’s wit and courage. As a reward, he gets to sexually possess her. All the main actors in all the films are white; those playing Indian characters are covered in brown make-up, performing an exaggerated Indianness that is 100% fictitious. The dances are not Indian, but very bungled attempts at Balinese dance. In the press text about Mani’s performance, Anthony George Koothanady writes: “a trained tyger trapped in Whiteman’s fantasy is the only real Indian in these films”.

What is a real Indian? Obviously, this question is absurd. But it has often been wielded by Westerners to discipline and control in the material world, in the realm of meaning, and their intermediary: state bureaucracy.

Photo: Paris Helene Furst

Mani, who hails from a family of rubber-tappers in a remote village in the northern part of Kerala, South India, describes himself as an intersectional, anti-national artist. In his nuanced and radical performances, Sajan Mani investigates how the body marked as Other is forcibly transformed into a site upon which dynamics of domination try to manage their own instability and insecurities. He has been “experimenting with [the] post-colonial black Dalit body in public space since birth”. “My tryst with my own body as a meeting point of history and present instigated me to concentrate on [my] body as a socio-political metaphor,“ he writes in his artist statement.

The Othering he denounces operates not only along the lines of race but also shade and caste. The latter is a mechanics of subjugation almost never addressed in liberal intersectional discussions in the West nor in art anywhere, which thereby invisibilises the complexities of casteist oppression that particularly the Dalit community experience (also in the diasporas), as evidenced by the most recent cases of horrific violence against Dalit women.

“Everyone who writes about the Orient must locate himself vis-à-vis the Orient,” Edward Said writes in Orientalism, in which he exposes the violence of Western orientalist modes of representation. Having flattened the Other’s body and culture into projection surfaces for white fantasies, whiteness has also crowned itself the sole legitimate expert on what is or is not authentic or pure enough.

“The Orient and Islam have a kind of extrareal, phenomenologically reduced status that puts them out of reach of everyone except the Western expert. From the beginning of Western speculation about the Orient, the one thing the Orient could not do was to represent itself. Evidence of the Orient was credible only after it had passed through and been made firm by the refining fire of the Orientalist’s work.”

Edward W. Said, Orientalism (1978)

When we first met two years ago, Mani recounted how a group of Germans once asked him: “Are you really Indian? We have seen Indians on TV and they are not as dark as you.” This reminded me of what a former boss of mine, a rich white German advertisement filmmaker, once declared about his frequent holidays and photo-safaris in India: “In my soul I’m really Indian!”

Photos: Paris Helene Furst

Whiteness is deeply unsettled by the uncontrolled encounter with the culturally and racially Other, who eludes traditional European rational understanding – and thus reveals its limits. The Orient and its people are a source of both fascination and anxiety, but, due to the illegibility of bodies, behaviours, culture, scripts, language, cultural signifiers, philosophies, it must be “contained”, which is what the parameters of Orientalism perform.

In these fantasy arenas, the Other (be it “Indianness”, “the Orient”, “Asia”, “Africa”, “Indigeneity”, …) and entire continents are reduced to a backdrop, grotesque or hypersexualised characters: a set of props, a narrative device for whiteness to grapple with itself and ultimately affirm itself. The body of the Other becomes a phantasmatic site on which anxieties are projected and cathartic narratives are hashed out.

In An Image of Africa (1975), his seminal critique of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Chinua Achebe denounces the “preposterous and perverse arrogance” of reducing Africa to a mere “setting and backdrop which eliminates the African as human factor. Africa as a metaphysical battlefield devoid of all recognisable humanity, into which the wandering European enters at his peril.” Through cultural texts and popular representation, the West has constructed Blackness as its antithetical Other, and the other racial-geographic realms of Otherness as liminal and therefore threatening.

The white gaze reduces the Other to an animal-like body, either wild and dangerous or domesticated, with an inner life that ranges from inscrutable to nonexistent. It serves the function of embodying the alterity in contrast to which whiteness defines itself as a seemingly stable cohesive identity, culture, and group. With the German state having only come into existence in 1871, Germanness has always been in various crises of self-definition. As Mani pointed out when we spoke about his performance a few days later, these three films (1921, 1938, 1959) were produced in three distinct periods in both film history and German history: silent black-and-white film during the chaotic year of post-WWI-hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic and the heyday of German expressionism; sound black-and-white film during Hitler’s Third Reich, the year of the antisemitic Kristallnacht mass murder pogrom; Technicolor sound film during the Cold War period of post-war reconstruction, two years before the Berlin Wall went up. The first two films were produced while India was still suffering British colonial rule.

Photo: Paris Helene Furst

At the end of the performance, having covered nearly the entire white paper surface of walls and floor, the artist contemplates the space for a few minutes, slowly lowers himself to floor level, lies down on his belly, his head on the floor, and crawls out of the space backwards. The fake turban slips off his head and remains on the floor, an empty enigmatic signifier1. His performance clothes, he later tells me, mirror the films’ “Indian Prince” costume, now shed, as he removes himself from this space.

Mani’s performance powerfully responds to the German colonial desire to control Indianness, by elegantly revealing its mechanisms through counter-montage and magnifying its greatest anxiety: the indecipherability of the racialised Other, who defies and resists decoding by the Western rational mind. He inhabits indecipherability as a space of resistance and defiant self-expression: the repetitive charcoal script on the walls and floor, Mani tells me a few days after the performance, is the word “LIE”, countless times, in Malayalam, his mother tongue.