The wide offer of online dance classes demonstrates how we can all stay connected to one another despite social distancing while dancing alone. On the complex interplay between closeness and distance in the time of Corona.

I’m sitting on a yoga mat alone in my living room in Düsseldorf where I’ve been staying since mid March. I can see around eighty people on my laptop screen, live in their bedrooms and dining rooms, in their kitchens and on their terraces. There’s nothing unusual going on here: participants are stretching, resting in cross-legged positions, talking – the things you do when you’re waiting for a class to start. Some participants greet one another. I see mothers with their children and spot friends from Vienna.

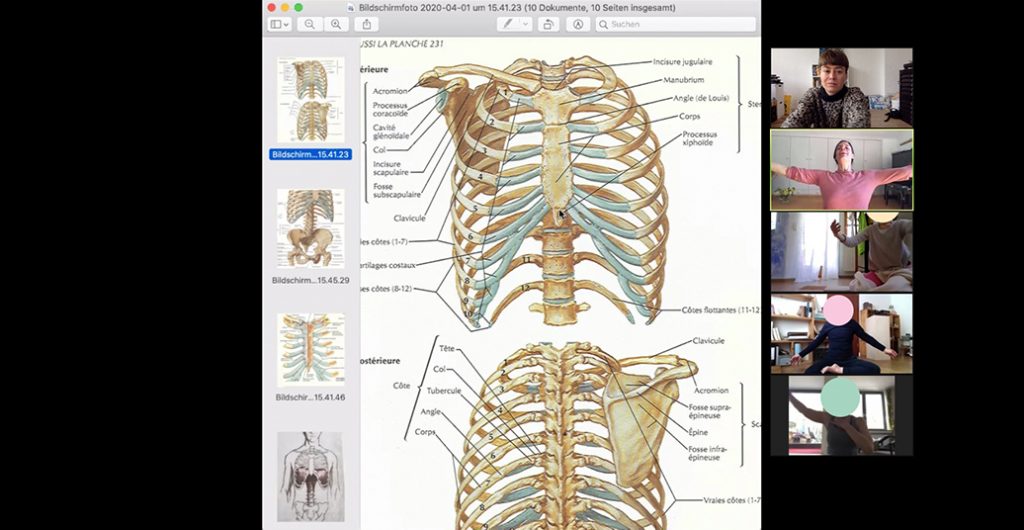

It’s not a coincidence that the focus of this first Body-Mind Centering online course, which Tanzfabrik Berlin has been offering since the decree to shut down studios, is the lungs: “I was a bit undecided about choosing the lungs as the topic for the first course”, Nina Wehnert, the BMC instructor, later tells me. “I’m sure it’s really important to feel our lungs right now. I went on the assumption that most participants did not have lung infections and were healthy, and that it could be therapeutic to sense their own healthy lungs. But at the same time I was concerned that I was stumbling onto something a lot of people are worried about right now – namely the fear that their own lungs could be infected.”

I inhale deeply and exhale slowly. My hands embrace my ribcage so I can feel how it rises and falls, how it spreads out – takes up more space in the room – and once again contracts. How much do both lungs expand when we breathe in? I feel how each breath sets my body in motion, how the movement from the apex of my lungs continues throughout my body. And I manage during the course of this hour to feel their expansion in my body out into the space beyond. Nina reminds us again and again to remain aware of our space-consuming three-dimensionality. “BMC is about relying on our body’s own intelligence and surrendering to it. It’s about intensifying the appreciation of our body. It seems important to me, especially in light of all the fears we’re being confronted with, to feel ourselves amid this uncertainty and be aware of our three-dimensionality.” How quickly we forget about it when we’re constantly staring at flat screens and the front sides of two-dimensional bodies – yes, we still have backs!

Tanzfabrik, DOCK 11, Marameo, the Somatic Academy Berlin and many other dance and movements schools responded immediately to the recently introduced contact ban and shifted to online classes. An experiment, since instead of physical presence in a studio, all you need is an email address, Zoom, and a more or less quiet space in your own four walls. Payment is (hopefully) made in the form of donations.

But what are the consequences of entangling digital technology with a kinesthetic experience? Could dance – including the different body techniques, the somatics – be “the kind of medicine our bodies need”, as dance critic Gia Kourlas hopes in the New York Times[1] with regard to current distance offers? And even more general: can real bodies physically and sensually communicate with one another in a technically transmitted and only virtually constructed mutual space?

Nina Wehnert shares the skepticism resonant in these questions: “I find one of the difficulties of BMC is that a lot is transported non-verbally in BMC classes and – a typical BMC term – in the ‘Mind of the Room’, so through the quality of the space. When I’m in a certain mood and move with my organs, then I move with a certain quality that I can’t necessarily name verbally, but which can be sensed by other people in the room. Something is transported at some level, which enters directly into the body. That’s how I also realize what my students are doing. I can look at how they’re moving, but I can especially feel what the mood is in the space. It is exactly this level which is currently lacking.”

We have to come to terms with this lack if we want to meet live but in separate spaces that can only be synchronized with the help of a software program. This enormous virtual space – 100 participants from the most diverse countries joined the second BMC class, there were more than 400 participants in a Gaga class from Tel Aviv – incites and tests our power of imagination. It distracts us and overwhelms us at the same time. Nina Wehnert comments: “I felt like I had to provide a lot more verbal instruction. In the studio, I transport a lot more through my own body and movements. Things which I must now convey just through a screen. But what participants see on the screen is not as meaningful as being together in a room.”

Given the circumstances of the Corona pandemic, the relationship between nearness and distance has become strange and unusual. Distance should no longer signify – a negative connotation – the lack of touch and even absence. Instead, transposed into a kind of virtual empathy and virtual intimacy, it should help to bridge the gap to the other (and to oneself) – making the absentee present. The Internet can bridge spatial-social distance, but hardly physical – meaning all that remains is the attempt to eliminate any distance to my own body? So I do Gaga.

“Listen to your body before telling it what to do” – that’s the idea behind Gaga and in the half-hour sessions offered every day by the Gaga community in Berlin. One of the most vital and beautiful qualities of Gaga is the sensation of flow: “The bones are floating inside the water of your body. Connect to the floating quality of your ribs”, Alvin Collantes, one of the Gaga teachers from Berlin challenges us. As if we’re floating in water – or as Alvin expresses it, sliding in oil or butter – we participants move forward as one, without standing still for even one moment during the half hour. A feeling of openness, also to the outside, a near dissolving of boundaries, structures, and forms spreads throughout my body. My self coalesces with an immersive landscape of oil, butter, water, bones, fascia, and muscle mass. “Gaga is always about being physically present together and being aware and sensitive together. It is a body language that involves physical bodies being together. That moment when you come together in a group, feeding each other information, sharing, sending and receiving information of how the body can become even more available.” However, he immediately limits the practice of togetherness in online classes. “This is something you cannot achieve staying in your house. Gaga is a lot about sensing what and who is around you and how our bodies change by seeing what is in front and what is around you. Something that is not possible when teaching online.” Nevertheless: “But beside that there are other parts of the movement language that allow you to connect to your body – the pleasure, the letting go, the passion to move, the ability to become delicate.”

And it works: even in spite of the physical absence of the other participants, I feel so much positive energy rushing through my body that I briefly forget I’m dancing alone at home. “I really believe in energy”, Alvin Collantes tells me. The simulated presence of the others bridges the real distance. My flesh and their virtual materialism merge together.

English translation by Melissa Maldonado

[1] New York Times, Critic’s Notebook, Gia Kourlas: „How We Use Our Bodies to Navigate a Pandemic“, 31 March 2020.