Every January, the Berlin dance audience flocks to the Sophiensaele for Tanztage, the annual inauguration event. The ten-day festival, which has existed for over twenty five years now, kicks off the new dance year by focussing on emerging choreographers making work in Berlin.

Artists featured in Tanztage are mostly alumni of Berlin’s dance and art institutions, including HZT, balance 1 and UdK. If the work is well received, it may be invited back – it is not uncommon for Tanztage debutants to be booked for a full production later in their careers. With no overarching theme, the festival is highly diverse. From sculptural interventions challenging audience interaction (Tchivett’s “Hollow Matters”) to TED Talk-style solos reflecting on race (Anjal Chande’s “This Is How I Feel Today”), no subject is out of bounds. With a tight production budget and limited rehearsal time, the works presented are often experimental or in the first stages of their development. That said, Tanztage provides fertile ground for seeds to be sown and plenty of intriguing ideas made up this year’s exciting programme.

As I search for an empty seat in the auditorium for Julia Rodríguez’ “By The Time You See This It’ll Be Gone”, I notice three performers, huddled to one side of the room, waiting. They are rather oddly placed, hardly even on the stage, and I presume they will move towards the centre when they begin performing. But they do no such thing. Almost imperceptibly, they begin to make soft, indistinguishable sounds with their mouths – whooshing, hissing, gurgling – their bodies still positioned at the edge of the room. Gradually, the humming turns into zooming and the buzzing turns into beeping. It’s the sound of cars rushing past on a busy road, hooting unapologetically at bikes and pedestrians. The criss-cross of tones and voices intensifies, the symphony of heavy traffic climbs towards a crescendo, and then… nothing. It is almost silent. But as the final ‘eep’ resounds, their tongues switch to a new soundscape. This time it is more like white noise, or many radios playing at once – maybe a scene from an accident, or a terrorist attack. With snatches of words and sentences now audible, they repeatedly draw us into new sonic plains, and then, without warning leave us dangling, clueless and in utter bewilderment.

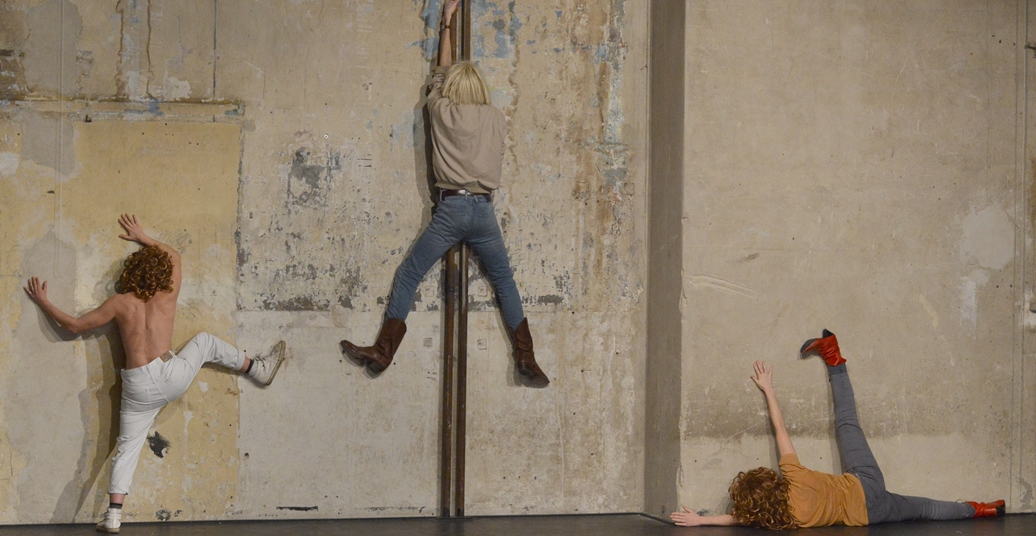

Making a break from the fringes of the space, Lola Rubio, now donning a wig with bountiful, bronze-tinted curls, drags her chair to the centre of the stage. She sits, her gaze fixated on the wall opposite her. She mutters to herself, like a crazy person, her fake hair full of secrets. She reminds me of a soul-searcher I once encountered on the U-Bahn, selling truths, teetering on the fine line between lunacy and genius. The others, now also wigged, soon follow. They cross the stage, careful not to show their faces, and, like magnets, land with their fronts against the back wall. At this point, I start to regret not having looked at their faces more at the beginning. I am too late and they will not look at us again, they will not give us the satisfaction of their gaze. They hang sideways from the building’s columns, they climb the pipes, they shout with all their might into the room’s corners – but their voices are muffled by the concrete. The state of emergency is tangible, but the emergency itself never quite materialises.

With “Nostalgia in Reverse”, Forough Fami orchestrates an altogether different setting. Neon tape divides the stage with a jagged line, dotted by shiny, angled funnels. Fami and fellow performer Michiyasu Furutani are kitted out in silver tracksuits and futuristic diving gear. Out of nowhere, a large, fuzzy, grey ball rolls in to take the spotlight, moving of its own accord. An eerie, disembodied voice starts to speak, as if belonging to the faceless sphere that sits, now motionless, in the middle of the stage. It feels as though we are lost somewhere in space-time, cruising on a rogue space ship inhabited by anthropomorphised objects and lonely intergalactic warriors.

With cinematic dramaturgy, Fami and Furutani pop in and out of the scene like weightless avatars. A steady beat drives them to run around the stage, orbiting like planets, appearing and disappearing in a zero-gravity limbo. There seems to be an inner-logic to this self-contained universe: one by one, the plastic props are stacked together, like in a 3D puzzle. Once the final piece is in place, the code is broken, Tomb Raider-style, and a neon techno-box emerges. Furutani enters it, tossing his limbs in time to the beat of the music, as if trying to escape the void that lies beyond. But rather than enhancing his dance, the sound overpowers it. The familiar image of a body bouncing to loud techno under dim light leaves no space for interpretation, and Furutani’s movement is momentarily dominated by its Berlin club-goer stereotype. The clownish moment doesn’t leave me dissatisfied, however.

When taking a look at the list of credits, I am impressed by the number of collaborators involved in this piece. The voice of each artist is clearly present, yet they have been merged together to create a coherent whole. It seems this fluorescent, evanescent microcosm is a meeting point of minds, collectively glitching and gliding into unchartered territory. All that is missing is the addition of NPCs or a touch of AI, but in this seamless simulation of the virtual vortex, would we even notice?