After her South-African township piece “Chatsworth” and her choreography for Yorgos Lanthimos’ Oscar winning “The Favourite”, with “Der Palast” Constanza Macras will stage her first premiere at Volksbühne under the interim director Klaus Dörr. But her engagement with the much debated theatre started years ago… Astrid Kaminski asks the famous Berlin-based, Buenos Aires-born choreographer about her process in becoming an urban choreographer.

Constanza, your pieces are fast-paced and energetic. Would you consider yourself an urban choreographer?

Cities and the choreography of urban life have always inspired me. When I was young and in New York for the first time, I started carrying a camera around with me and shooting the city from high buildings and street corners.

Like a sniper.

Like a flaneur-voyeur with a camera. You know, all the images for “Megalopolis” [premiered in 2010 and part of the Volksbühne’s 2019 program] are sourced from the material I gathered through the years.

For your new production “Der Palast” Tom Hunter photographed the cast, including technicians, combining the style of classical master paintings and urban landscapes. What about you, do you still take pictures?

The way I used to photograph feels obsolete now because of all the mobile phone traffic. It’s not special any more. When I started, it was something else. I was dressing nicely in order to distract the people from the camera which was quite big and sometimes pointing directly at them. I would be standing there, next to a high building, or on a street corner, shooting everything with a deadpan face – even policemen. It was quite intrusive!

Did you grow up in an immigrant, a working class or a bourgeois environment?

My father came from an immigrant background. My grandfather immigrated from a tiny village on Rodhos island in Greece to Argentina and he was very humble and poor. But my father was ambitious and he wanted to get out of the social environment he came from. Education was free in Argentina and he studied economics and anthropology. He made it to the best university and even skipped a year. When I grew up, we were well off: we had a house with a garden and everything. Even so, when I was 16, I started working immediately because our family had this working culture. I was a waitress, which was unheard of for middle-class girls. I was really obsessed with work. I enjoyed engaging in different kinds of labour as it allowed me to meet different people, and I needed to make my living somehow.

How was your neighbourhood?

I was born and raised in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, an hour away from downtown. My neighbourhood was pretty empty when my parents moved there – I remember a little farm with cows and chickens – but it expanded quickly. When I was in high school, I started to take dance seriously and I took classes in different downtown neighbourhoods. Between classes, as I was too far from my house, I passed the time in bookstores. Buenos Aires used to have and still has some amazing bookstores. But it was also rough – I liked these different moods. In the 90s, it got more and more violent and dangerous, especially in the centre of the city. People entered the cafés with guns and we had to give them everything we had. It was the time of the “Natural Born Killers”… The year I left, it got worse. It was no longer a question of “Don’t go there because it’s dangerous”, but rather: you could get mugged anywhere any time.

I don’t want to be a slave of the cities.

Let’s skip Amsterdam and New York and take a look at your first years in Berlin. You were living in a Prenzlauer Berg room without heating and electricity…

I started in Schöneberg. When I first came to Berlin in 1995, I had a job with a Spanish company at Hebbel Theatre and everything was cared for, including a beautiful apartment on Eisenacher Straße. After that, when I came back in late 1996, I rented an apartment on Kastanienallee [in Prenzlauer Berg] and I decided to concentrate all my energy on making my first dance piece. I had no money. My electricity and phone lines were cut off for two months, but I did not worry too much. I was very sociable, and friends would come by anyway. When I wasn’t there, I would find a bottle of wine, some notes or flowers at my front door. So it wasn’t at all bad.

Was it just the low costs that made Berlin interesting for a young artist?

Berlin was undergoing a moment of change, and the not knowing how it would develop was exciting. Of course we could already see the ghost of gentrification, but the blooming of things was overwhelming – the parties, the artistic energy… And as a young artist you could also have easy access to professional venues, like Sophiensaele and Hebbel Theatre, and learn how to set up and stage a piece. In a city like New York, these conditions seemed insane. Even though I like New York, I always knew that I would not devote all my life to the costs of the city. I don’t want to be a slave to the city.

Was it this journey into the unknown that led to all the space metaphors? Sasha Waltz created “Allee der Kosmonauten”, while one of your early pieces is called “MIR” – like the Soviet space station.

Having grown up in Argentina during the Cold War, I was discovering the east and everything that was behind the curtain and thus also the space program of the Russians. While making “MIR – A LOVE STORY” I was inspired by the film “Out of the present” by Andrei Ujica, a documentary about a cosmonaut who was in space when the Soviet Union became Russia. The film was fantastic. Very funny, too. At that time, we still felt adventurous in the eastern part of the city. My “Western” friends from Eisenacher Straße would not visit me in the east and I was like “Why??! This is the most interesting part of the city!” For example I used to go to a Peruvian restaurant which was located inside of the Karl Liebknecht house. Nobody went there – only me, and the friends I brought there. I celebrated every birthday party there. The food was very good and it was so special with all the socialist paintings and the mix of decorations. It was also very close to Volksbühne, where I tried to see everything. I loved discovering the city with them when I was part of “Rollende Road Show”: Lichtenberg, Marzahn, Märkisches Viertel and Neukölln. You know, in those times, Neukölln was completely out of the picture. But it was a relatively open neighbourhood. Imagine whole families, mostly Lebanese, sitting around in plastic chairs and watching a theatre piece by René Pollesch!

Pollesch in Neukölln. This was before my time.

It was in the context of the “Rollende Roadshow” [starting 2001], a project by Bert Neumann und Hannah Hurtzig from the Volksbühne that entered working class neighbourhoods.

And you were involved? Was this when you made “Scratch Neukölln” (2003)?

Yes, it was a three-year project and I was involved. It was in this context that I met the kids with whom I did “Scratch Neukölln” later on. I have to say that the “Rollende Road Show” very much shaped the way in which I work. But the first show I created in this context was a piece about folklore, which was for some of Johann Kresnik’s remaining dancers [Kresnik worked at Volksbühne from 1994/95].

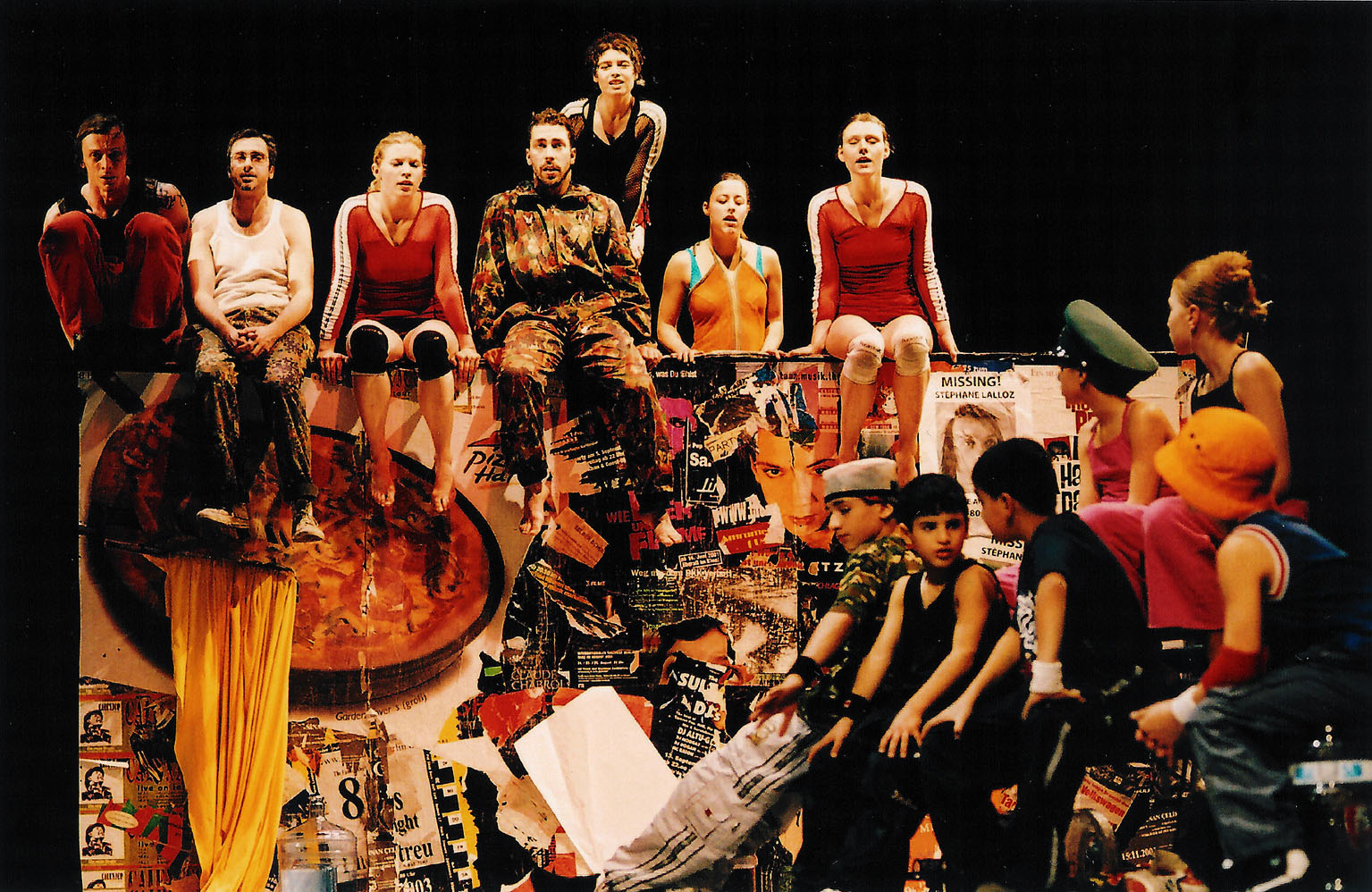

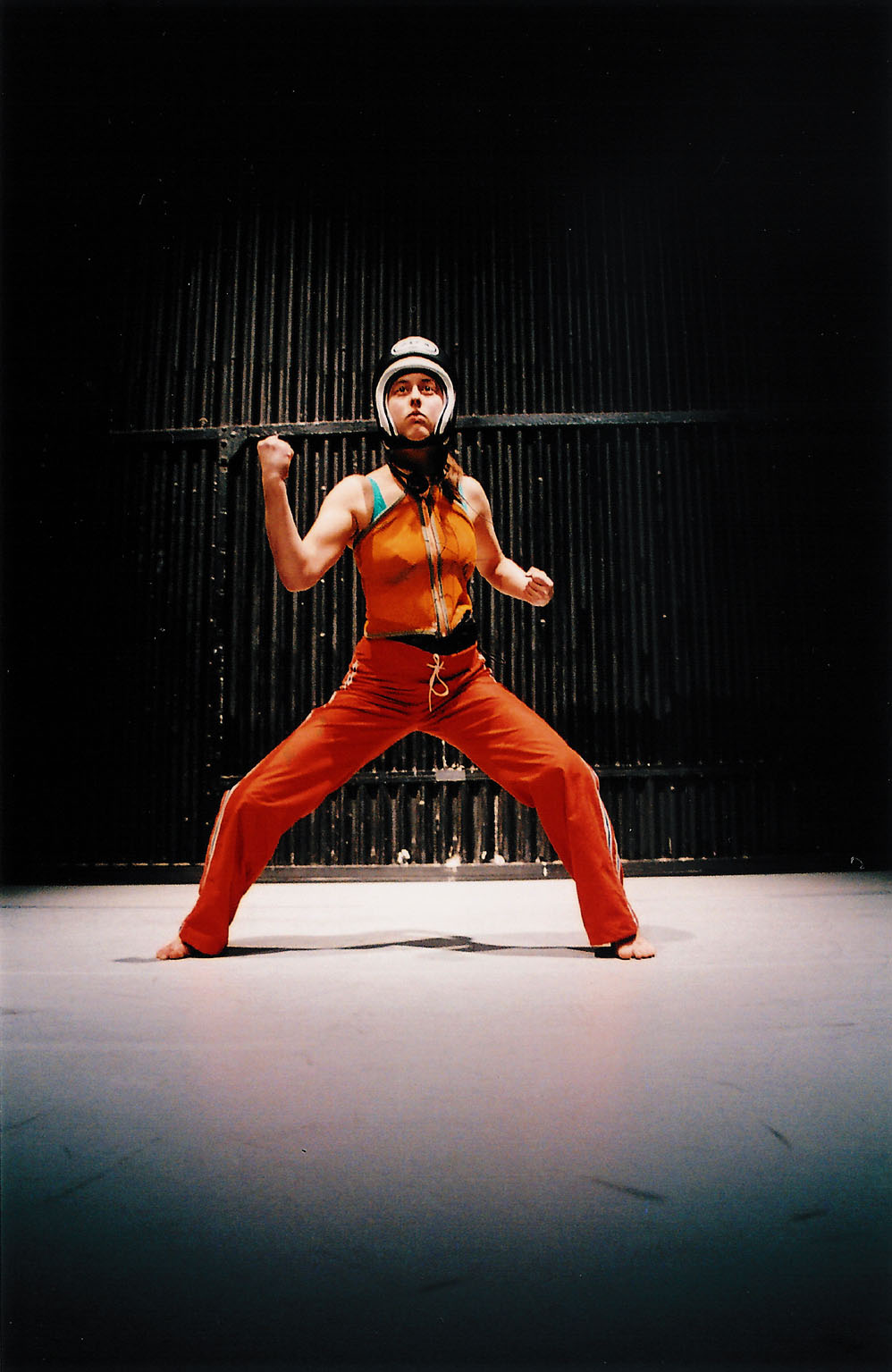

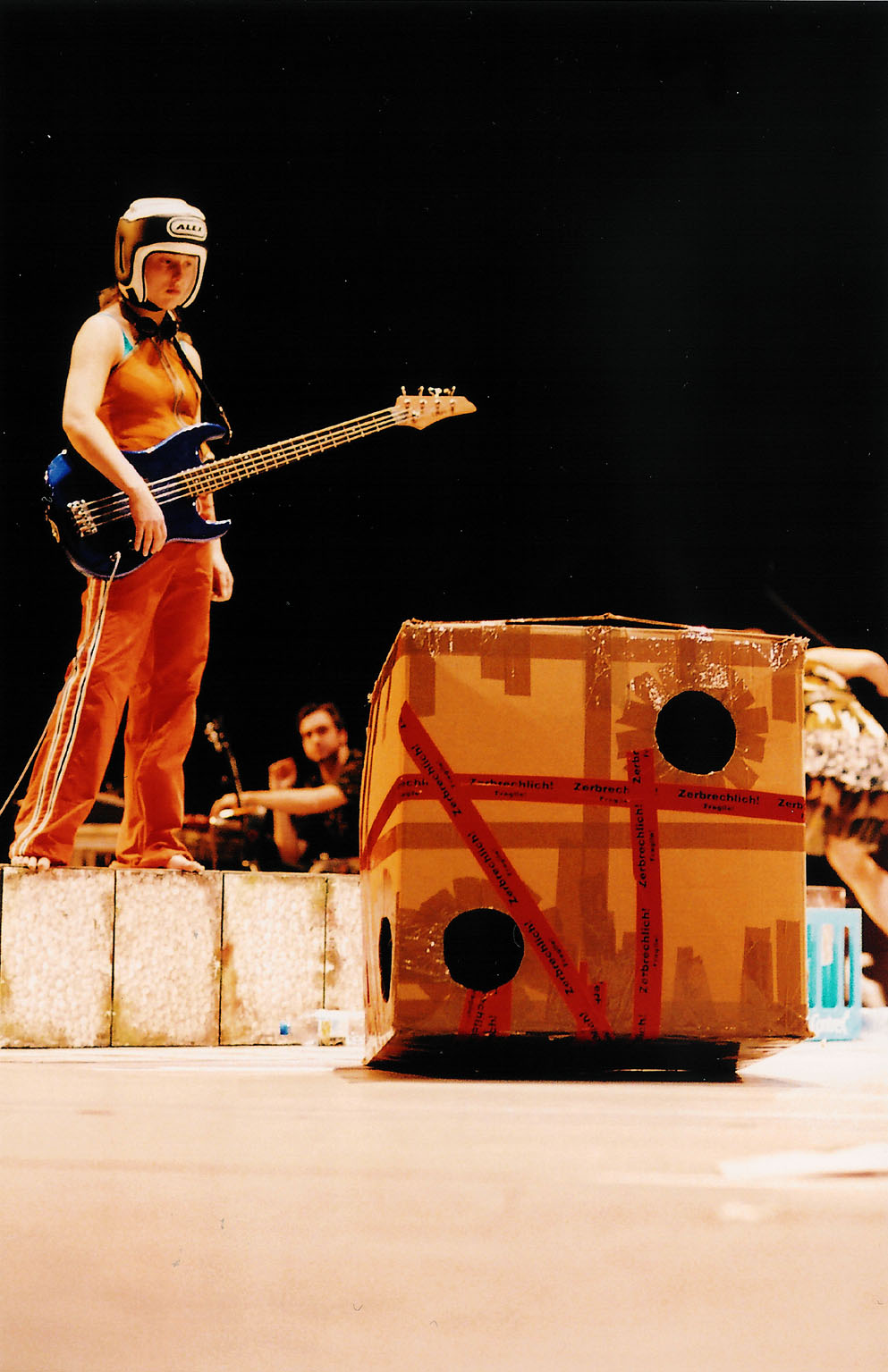

„Scratch Neukölln”, Constanza Macras_01©Aurel Thurn

„Scratch Neukölln”, Constanza Macras_04©Aurel Thurn

„Scratch Neukölln”, Constanza Macras_03©Aurel Thurn

„Scratch Neukölln”, Constanza Macras_02©Aurel Thurn

I would love to go into detail but let’s make another jump. Now, many years later, you premiere “Der Palast” at Volksbühne. Berliner Festspiele recently developed a program on the “Palast der Republik” – the central, governmental building of the GDR including socialist ideas of a so called “People’s Palace” and a “Palace of Cuture”. Thirty years after the wall between East and West Berlin fell, Berliners naturally associate “Der Palast” with this GDR landmark which no longer exists.

It seems you can found a company there in 24 hours.

In Berlin, palaces are controversial. They stand for the changes as well as for the persistence of things. The Palast der Republik was very controversial, and the same holds true for the Humboldt Forum which replaces it. In this sense, Volksbühne is also a controversial palace, and, especially in recent years, has become a palace of change. Furthermore, you’ll find the social palaces of Berlin, such as the Palasseum in Schöneberg or the ZentrumKreuzberg at Kottbusser Tor, which are similar models of social housing that cross the streets. Now, both of them are gentrified, which is just crazy…They were supposed to house low income people in the city centre!

For “Der Palast” you also researched the criminality of gentrification in Berlin. What did you encounter?

Following the case of Dieffenbachstraße – where people managed to make the city buy their house in order to save it from investors – we were interested in the question: Where do all the investors come from? The village of Zossen in Brandenburg plays an important role in this. It enjoys a remarkable tax reduction. It’s like the Panama of Brandenburg – 1500 companies in a village of not even 20 000 people! It seems that you can found a company there within 24 hours. Doesn’t that sound alarming? I have a company, DorkyPark, and the paperwork took us at least a few weeks… I also discovered the website and artistic project “Haunted Landlords”, which displays the methods investors use to chase the inhabitants away. The measures range from halting garbage collection or cutting the water supply to purposefully leaking carbon monoxide. It gets really dark. People who depend on social support and have to move out of their houses can’t find flats any more. Their social benefits are too low. Some people who can’t afford the rising rents even live in “Lagers”. I met a family who had to move to an emergency location for refugees, without a kitchen and with a shared bathroom …

How does this knowledge inform your choreographic language?

In terms of structure, I work on the one hand with abstract dance and on the other with a vocabulary from global TV shows like “Dancing with the Stars”. These kinds of formats are reproduced everywhere in the world and they bring about new archetypes like the “judges”. This kind of cultural flattening is very similar to how gentrification works.

Is criticizing enough or do you have strategies to resist?

It’s part of how we live nowadays. But we can make small choices to disempower big companies. Yet, it requires a lot of self-discipline and exercise. Stop buying from the big companies!

Stop buying with one click!