“STRICKEN” (“KNITTING”), 4 – 7 October at Ballhaus Naunynstrasse, by Magda Korsinsky attempts to unpack the complex relations between a black girl and her white grandmother and explores the ways in which racial and political issues manifest in the intimate relationships between family.

I arrive totally drenched, cursing the rainy autumn weather. My shoes are wet but at least my stomach is full. I gather myself as best I can for the show. Waiting for the doors to open, I look over the programme; the piece is performed by Hilla Steinert and Naê Flor Selka de Paiva. I note with interest that six interviews with black German women about their white grandmothers formed part of the research for this dance performance.

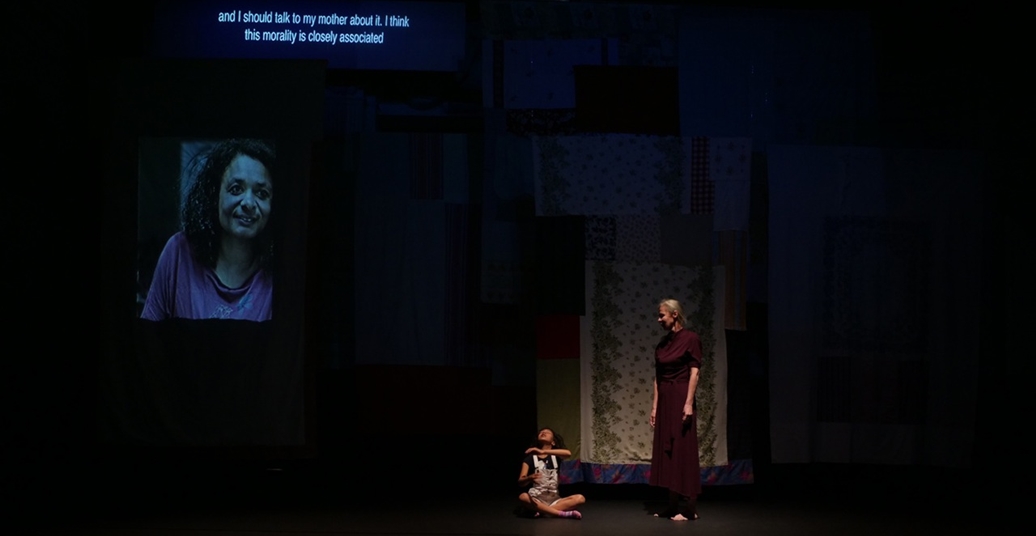

As it turns out, these interviews are an integral part of the work. The space is held by a soft hush of many overlapping voices, which I realise later are the voices of the six women interviewed, who are present before the performers are. The stage is empty except for several, very large pieces of fabric with light, floral patterns hanging towards the back of the stage, resembling bed linen hanging up to dry. The voices fade and the lights go dark. A single voice begins the show with a description of her grandmother; other voices follow, also telling stories of their grandmothers. English subtitles are projected above the stage and I am aware (and slightly concerned) that my attention will always be split in two.

Naê Flor Selka de Paiva, who must be about 9 or 10 years old, bursts on to the stage, skipping in a classically girlish way, the buttons on her dungarees jingling, providing the constant sonic effect of a kind of fairy-child. I am not so accustomed to seeing children on stage and initially, I am entranced by both her unaffected movement quality and her direct, slightly flirtatious gaze towards the audience. I notice Hilla Steinert, presumably playing the grandmother, watching from the corner. Steinert and de Paiva settle into their choreography, which consists largely of movements abstracted from domestic gestures: folding laundry, carrying a basket, reaching up to hang something out, cleaning, cooking, brushing hair — the deeply familiar dance of kitchen and home. De Paiva has one eye on Steinert, imitating her, and although for a while it’s interesting to watch these two different bodies perform the same tasks, the sequences do not seem to develop beyond this, nor does the relationship between Steinert and de Paiva expand beyond a few glances and a mild warmth. It’s an intimacy that never fully arrives.

A composition of six films depicting the women interviewed is projected onto the hanging cloth and woven into the performance. We see the faces belonging to the voices and later, I look for their names in the programme, but I cannot find them. This troubles me, since their thoughts, words, and presence form such a big part of the work. For the first time since moving to Germany from South Africa, I am encountering topics of racism, of whiteness, of Africa and Europe on stage, discussed with a frankness and sensitivity by women who experience these historical complexities daily. They speak of the difficulties of negotiating broader racial politics within the intimacy of family. One woman points towards the very real fear of what it means to be a person of colour in Germany’s current political climate. Another woman laughs as she reminds us that the term ‘intersectionality’ does not just belong to academia; she lives it everyday. It’s not so often that I come across this kind of discourse in Berlin and yet, it is such a vital conversation. Topics of feminism, whiteness, colonisation, Nazi ideology and intergenerational trauma flow in the space. Each word is incredibly important, each viewpoint is unique. They all point towards the hidden histories of black lives and politics in Germany.

Despite the richness of these conversations, they do not translate to what’s happening on stage. The choreography often feels weak in relation to the films and I can’t help but wonder why Magda Korsinsky, both a visual artist and choreographer, finds it necessary to use the medium of dance for this particular project. While I understand the importance of the body in a work such this, since race, gender, and identity are so inscribed onto the body, the movement itself feels somehow underdeveloped. In fact, the strongest part of the performance for me is when Steinert and de Paiva stop dancing, and sit down and watch the videos with the audience. A white older woman and her small brown granddaughter, watching this chorus of complex and eloquent conversations about race and family. It is a very powerful image, and, in a way, that would have been enough.